The internet buzzes with a persistent rumor: tennis balls contain sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), a dense gas touted for its ability to enhance bounce and longevity. This claim, however, is riddled with contradictions, as SF6's shock-absorbing properties seem to clash with its purported bouncy nature. This article delves into the heart of this intriguing mystery, exploring the evidence—or lack thereof—supporting the SF6 tennis ball theory. We examine firsthand testing, analyzing commercially available tennis balls, vintage products, and even a gas spring apparatus to determine the truth behind this widespread online belief.Our investigation takes a multifaceted approach, encompassing a comprehensive search for SF6 in various tennis ball brands, a density test to detect the presence of the gas, and a detailed comparison of SF6's performance against other gases in a controlled environment. The findings uncover unexpected results, challenging the initial assumptions and offering insights into the science behind a tennis ball's bounce, the economic factors influencing material selection, and the significant environmental implications of certain gases. Prepare to unravel the mystery of SF6 and the surprisingly complex physics behind the seemingly simple tennis ball.

Pros And Cons

- Increased longevity due to slower diffusion of sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), potentially keeping them pressurized longer.

- Increased cost of production.

- Fewer sales due to longer lifespan.

- SF6 is not used in modern tennis balls.

Read more: Top 5 Dunlop Tennis Balls: A Buyer's Guide

The Myth of SF6 in Tennis Balls

The internet is rife with claims that tennis balls contain sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), a dense gas often called 'doop forged gosh'. These claims suggest SF6 is responsible for the ball's bounce and longevity. However, the purported shock-absorbing properties of SF6 seem to contradict its supposed bouncy nature, raising questions about the validity of these assertions.

Many sources, from online forums to industry reports, support the SF6 tennis ball theory. Several patents even detail the potential benefits of incorporating SF6 to improve the ball's lifespan by slowing down the diffusion of air molecules through the rubber. This is crucial because tennis balls are pressurized, and air naturally diffuses out over time, reducing their bounce.

The Investigation: Searching for SF6

My own investigation began with an extensive search for commercially available tennis balls containing SF6. This involved purchasing various brands from local stores and online retailers, including less common brands like Green Dot and Orange Dot balls. I even acquired sealed vintage tennis ball cans from eBay, hoping to find SF6 in either the balls or the cans.

The search was exhaustive but ultimately fruitless. No traces of SF6 were found in any of the tested tennis balls, despite the claims and patents suggesting its inclusion. This led to speculation about the reasons behind the absence of SF6, despite the seemingly logical benefits outlined in the patents.

The Density Test and a Surprising Result

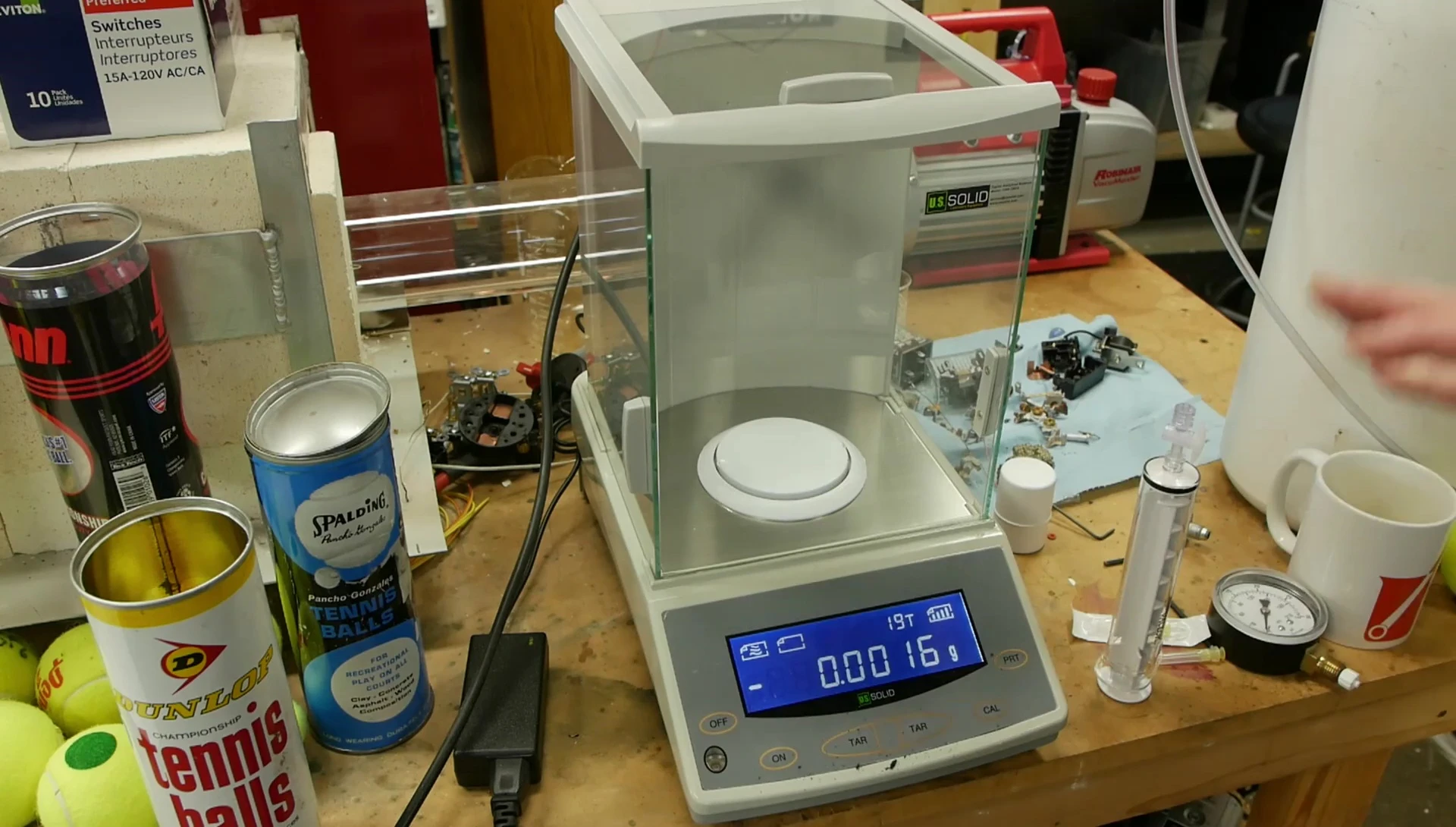

To detect SF6, I employed a density test. Since SF6 is five times denser than air, precise density measurement can reveal its presence. I used a highly sensitive scale to weigh a syringe before and after filling it with gas from a pierced tennis ball.

Surprisingly, the syringe weighed less after filling it with gas from the tennis ball. This wasn't due to a lack of SF6 but rather the buoyancy of the gas in the air. The test inadvertently measured the buoyant force, demonstrating how a vacuum is significantly more buoyant than even helium.

SF6 in Nike Air Products: A Different Story

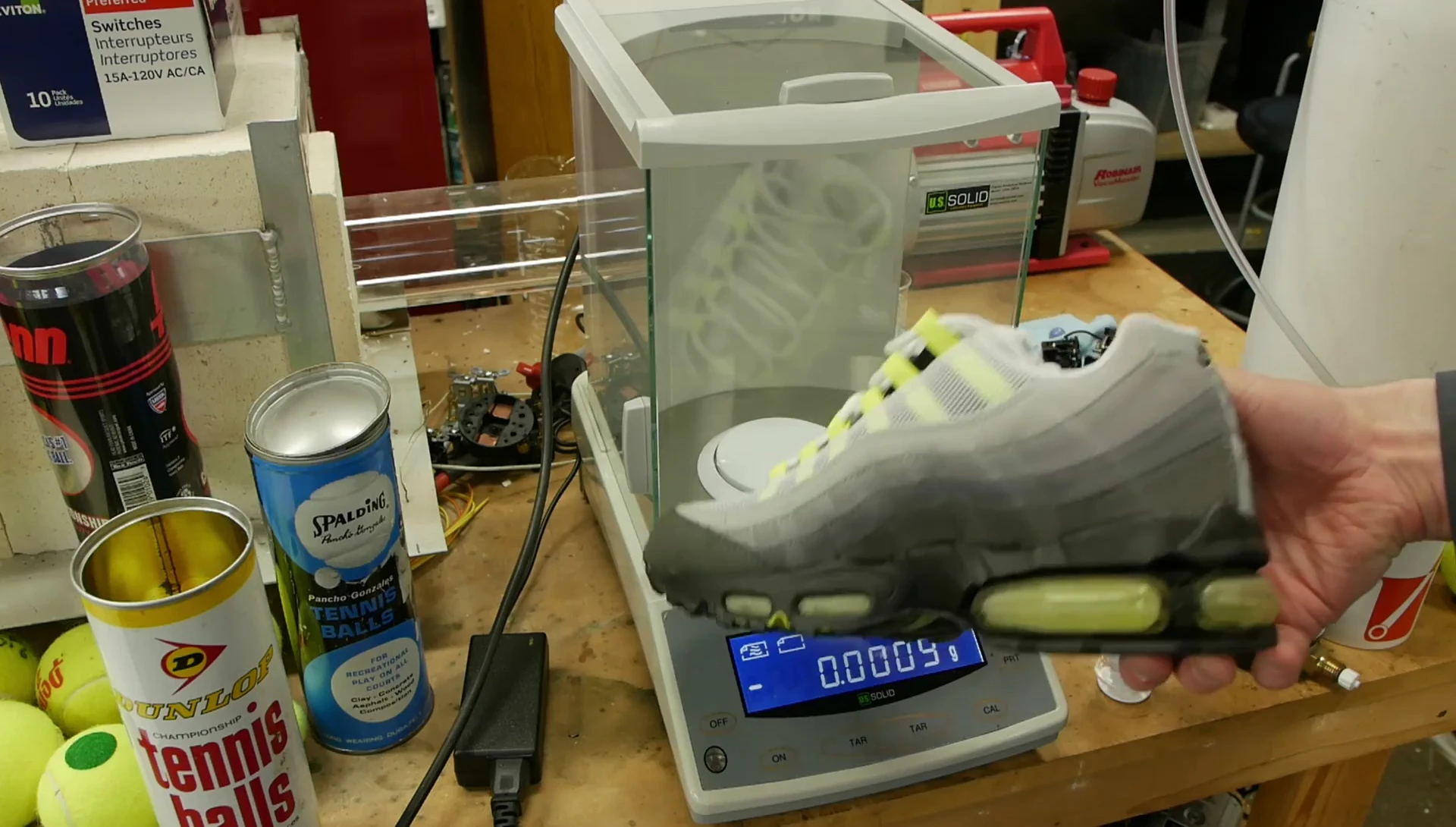

Unlike tennis balls, some Nike Air products were indeed filled with SF6. I personally tested a vintage Nike Air shoe and found traces of SF6 remaining. However, Nike discontinued SF6 use due to its potent greenhouse gas effect, 20,000 times stronger than CO2.

The economic realities differed significantly. The cost of SF6 and the longer lifespan of the resulting products made its use viable for Nike Air, unlike the low-profit margins of tennis balls. This highlights how the practicality of SF6's inclusion depends heavily on the specific product's market and manufacturing costs.

Testing the Bounciness Claim: A Gas Spring Experiment

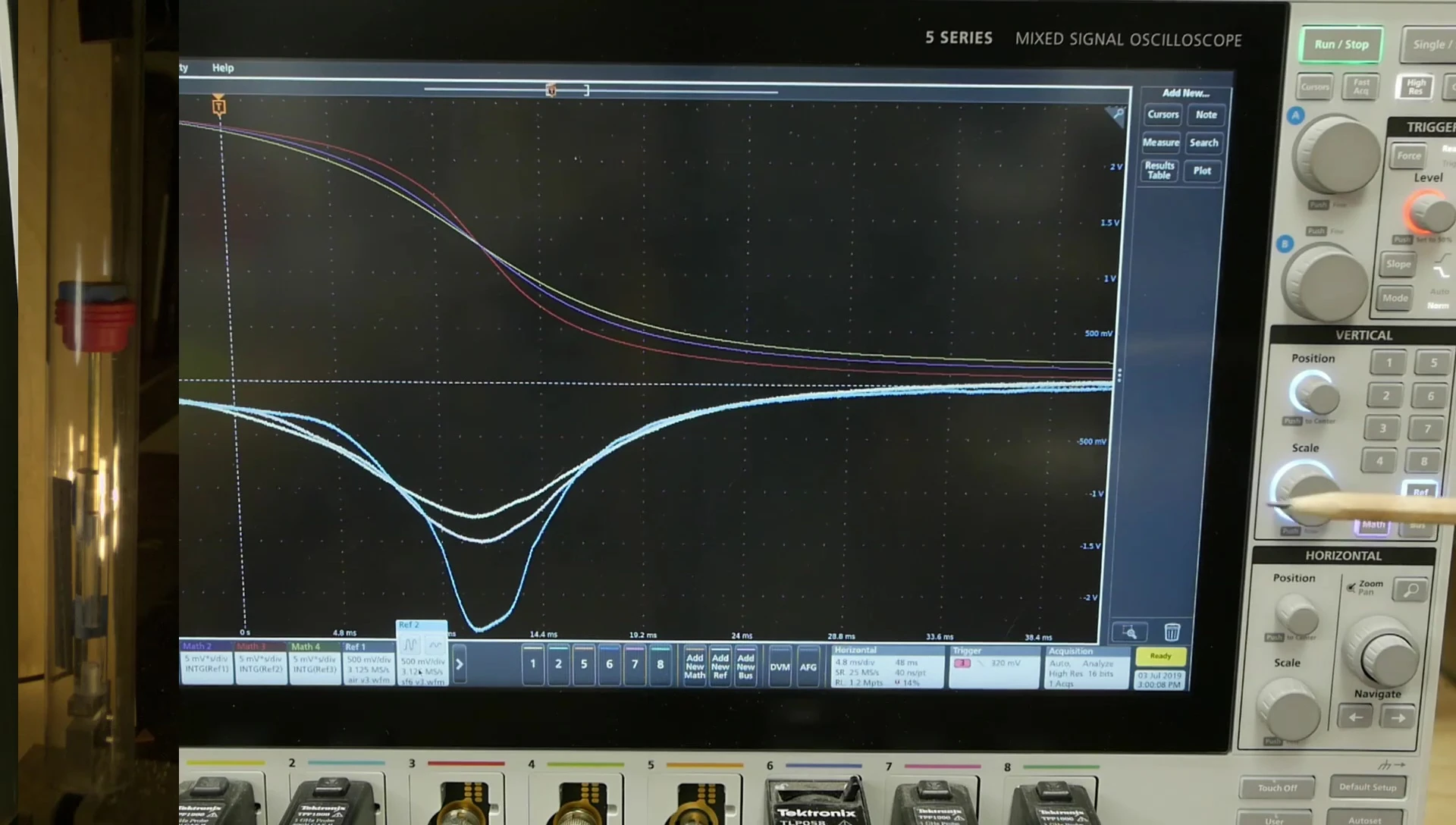

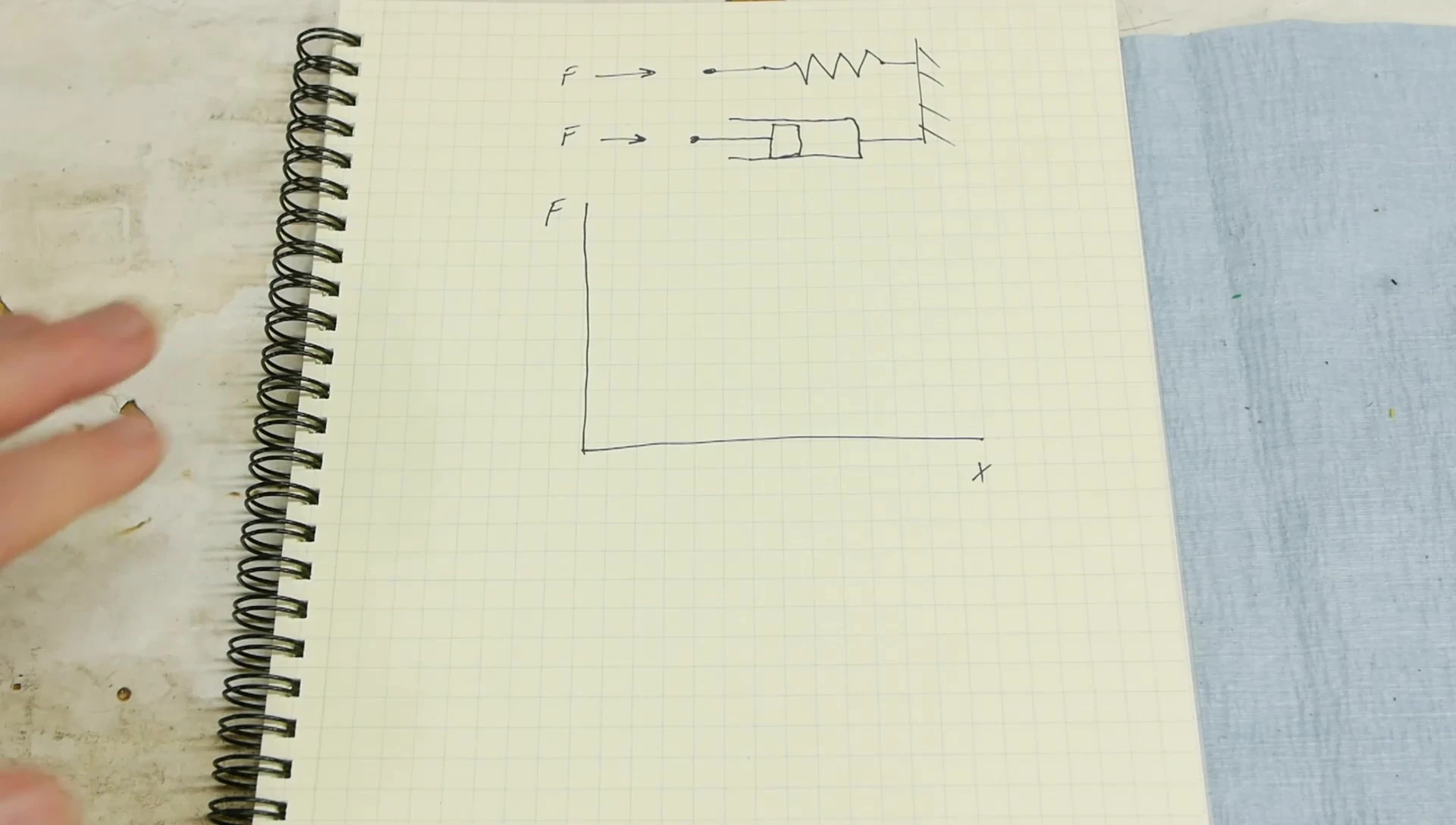

To directly test the bounciness claim, I constructed a gas spring apparatus with a free-floating piston and cylinder. Different gases (SF6, argon, and air) were tested by dropping a weight onto the piston and measuring the force and rebound height.

The results showed SF6 was not the ideal shock absorber. Argon produced a smoother, lower peak force, indicating better shock absorption. Surprisingly, SF6 had a higher peak force and the highest rebound height, demonstrating that while not the best shock absorber, SF6 does produce a bouncier result.

The Science Behind the Bounciness

The difference in gas spring behavior stems from the gases' differing gamma coefficients. SF6, a large molecule, has a lower gamma coefficient, meaning it heats up less upon compression than simpler gases like argon. This leads to a more hyperbolic force-distance curve, softer initially but much stiffer later on.

Argon, with its simpler atomic structure, behaves more linearly, mimicking a metal spring's response. The lower gamma coefficient of SF6 translates to a higher peak force and a greater rebound height, explaining its superior 'bounciness' compared to other gases.

Conclusion: SF6's Role Debunked (Mostly)

My investigation revealed no evidence of SF6 in commercially available tennis balls. While patents suggest its use for longevity, the economic impracticality likely prevented its widespread adoption. However, the gas spring experiment demonstrated that SF6 creates a remarkably 'bouncier' effect than other gases due to its unique low gamma coefficient.

SF6's use in specific applications like older Nike Air products highlights its potential benefits, though its detrimental environmental impact led to its discontinuation. While not found in tennis balls, SF6's properties make it an interesting material, albeit one with significant environmental consequences.